I stumbled across this video recently. I highly recommend you watch it before reading this.

It's a bit hard to describe, but essentially it talks about how you might have two very different model architectures generate the same output yet be quite different under the hood.

One — the good network — encodes generalizable features of the output. In the video (which is a discussion of a paper you can find here) this is shown with a skull as an example. The good network's weights would encode features of the skull, such as the two circle areas where the eyes go or the circle that encompasses the outline of the skull.

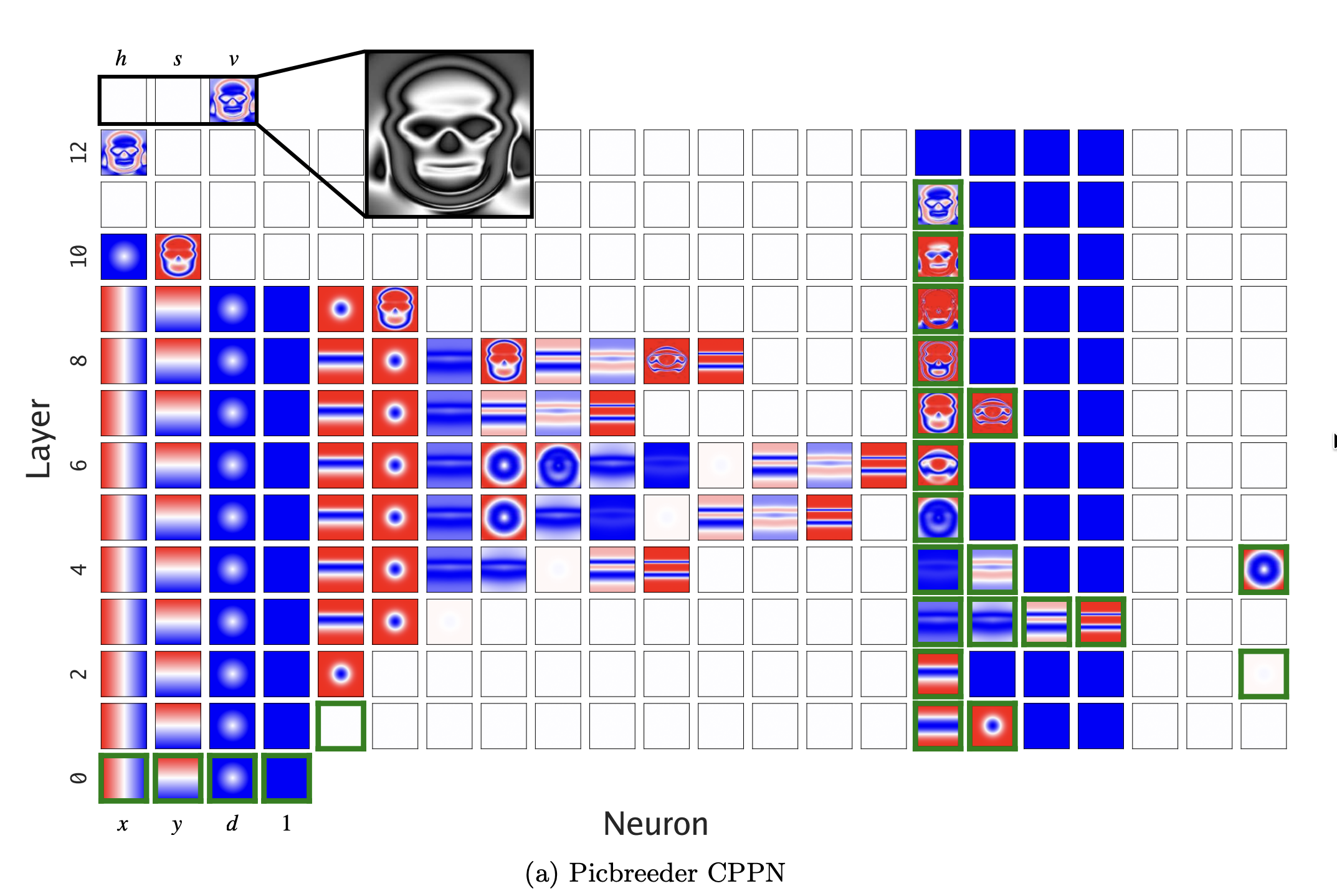

The 'good' network. The rectangles in the image show different weights at separate layers.

The 'good' network. The rectangles in the image show different weights at separate layers.

The 'bad' network didn't learn this. Its weights encoded far-apart, convoluted representations that captured some of the rough shapes of the skull. Yet they were both able to output the exact same target image they were originally trained to make.

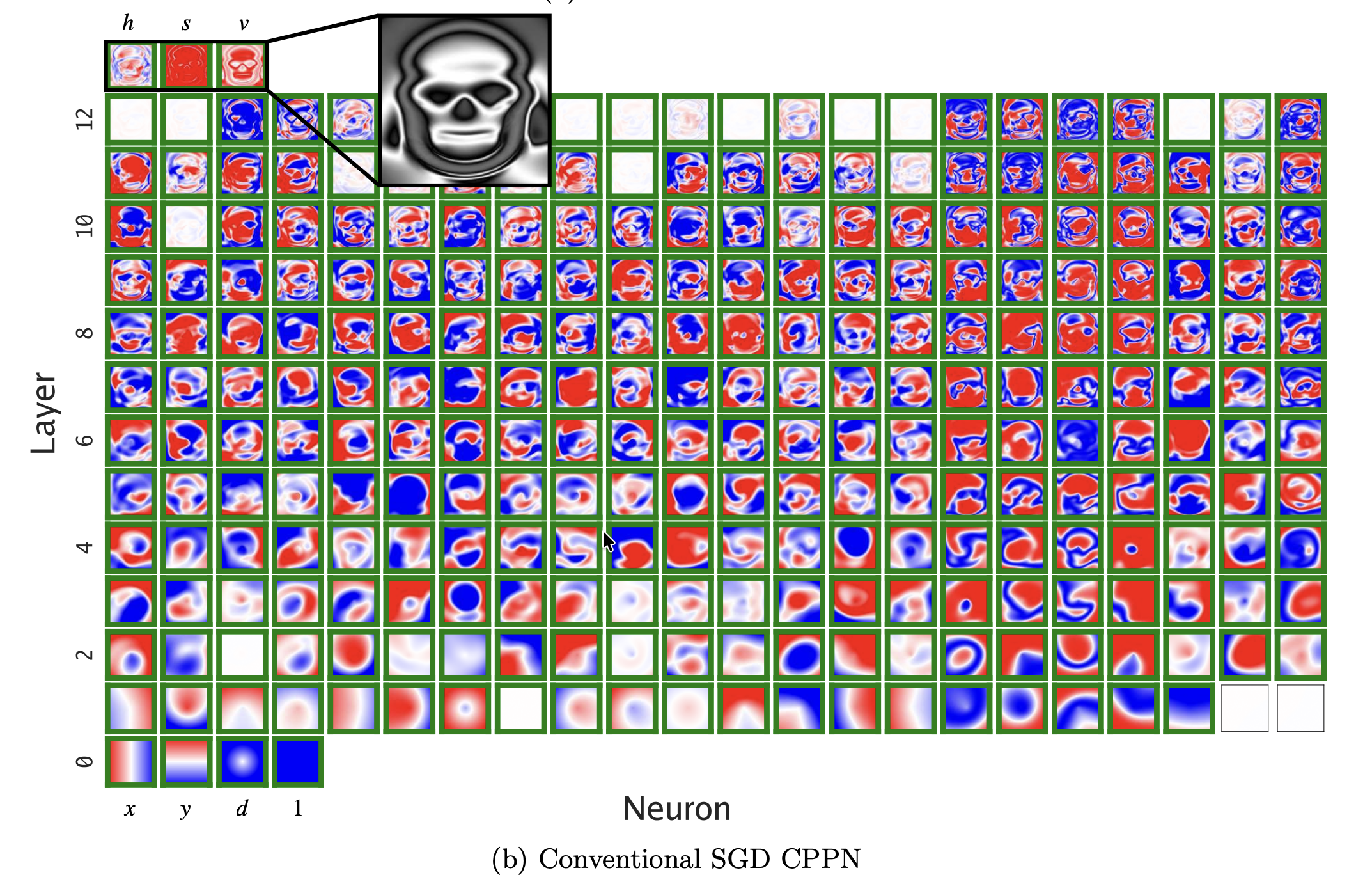

The 'bad' network. Its weights are blurry, disparate, and individually hold no meaningful information or features of the skull.

The 'bad' network. Its weights are blurry, disparate, and individually hold no meaningful information or features of the skull.

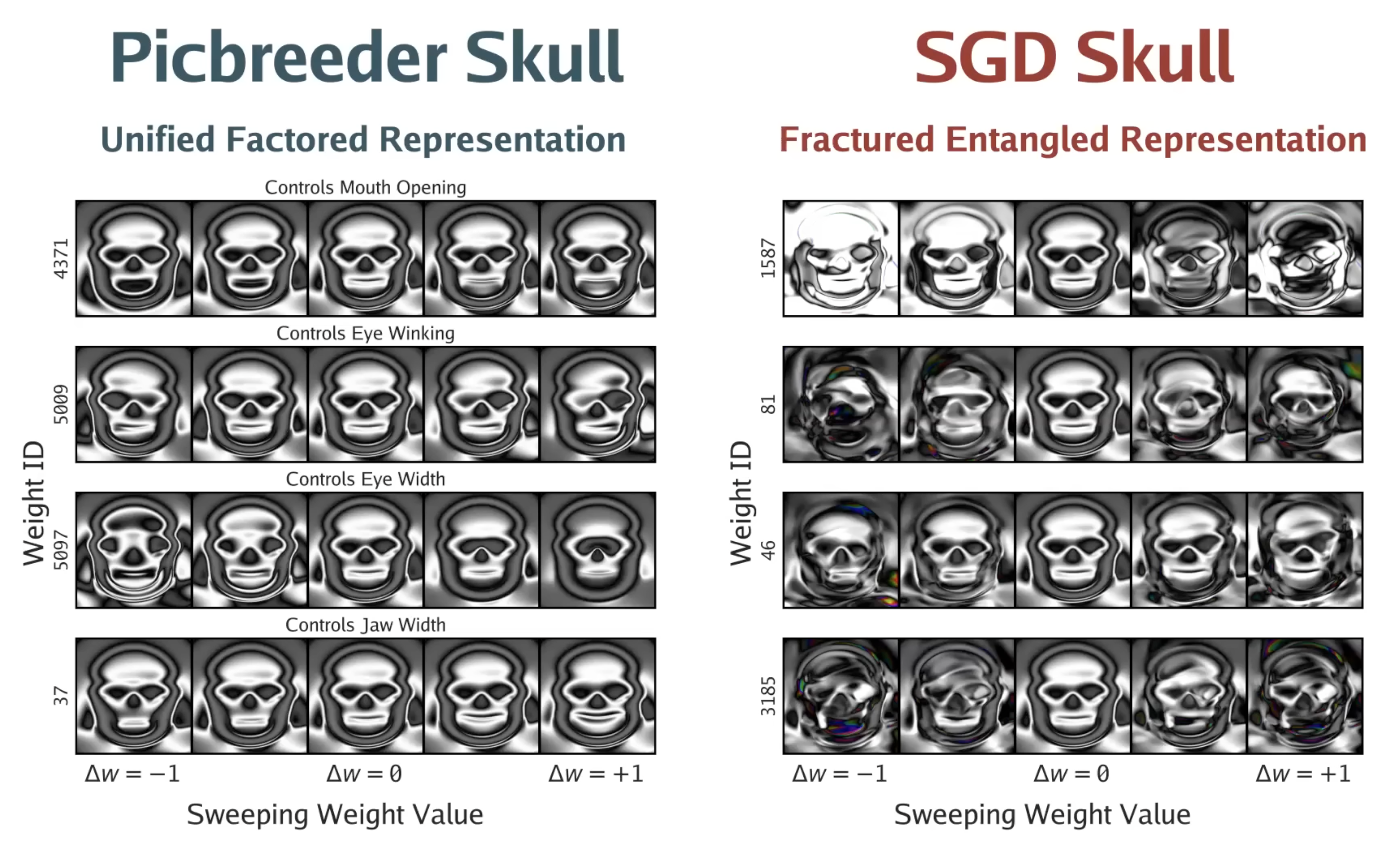

When each network was tasked with creating a mutation of the skull, varying the size of the eyes or the width of its jaw, the first network generalized well, while the second network distorted its outputs and didn't adapt well to the new changes.

The left side of the image shows the first 'good' network's output when varying the skull features. The right side of the image shows the second 'bad' network, where the edges especially are heavily distorted and unrecognizable.

The left side of the image shows the first 'good' network's output when varying the skull features. The right side of the image shows the second 'bad' network, where the edges especially are heavily distorted and unrecognizable.

Later on, the video shows how large language models exhibit similar behaviors — failing to generalize to very similar yet slightly modified problems from those they were trained to solve because they are trained to average out or 'mimic' what they observed in their training distribution.

Since the underlying architecture is based on brute-force pattern recognition and heuristics, they do not acquire the same logical and mathematical skills that help humans generalize similar problems.

This got me thinking. What is intelligence, really?

First, let's define a common language around intelligence. As I see it, intelligence is the ability to solve problems given a goal and objective constraints.

Second, defining most things requires answering some basic questions around where, why, how, and what.

I'll be talking more around the 'what' and 'how' here. Finding out where intelligence came from is a job I will be leaving to the anthropologists and evolutionary biologists. The 'why' will come from the arguments for the what and how later down the line.

Since the 'what' is already (sort of) answered above, I want to touch on the 'how', as I think it's more related to the very deep questions around the emergent properties that characterize biological systems.

I believe talking about intelligence inherently is talking about a question of nature vs. nurture. If we were to say that intelligence is a matter of nurture, it is implied that intelligence is a deterministic algorithm that each of us comes pre-loaded with.

Say, if I said that any one person placed in the right economical and educational circumstances can achieve some specific outcome — or in other words, that intelligence is distributed equally yet opportunity is not — the biological backdrop for this argument is that there is a blueprint for intelligence that is universally shared in the genome of the human species.

In machine learning terms, there are weights (presumably at the biological level, in our genome) decoded into the way that the human body is made that are universally shared and only need the right circumstances to be cultivated and made to perform at very high levels of performance.

In constrast, if we were to say that intelligence is a matter of nature, perhaps unintuitively, we would be saying that it is a stochastic process (although this doesn't imply it is outside of our control, as I'll elaborate more on later). This would seem to be supported by the fact that there is a general tendency that, for any population, there will emerge a 1% with individuals from very poor and disadvantaged backgrounds, going against the argument above on nurture as a necessary condition for intelligence. Some people regardless of circumstances might just be better-able than others (discounting for luck).1

These individuals generally aren't the norm, but their existence would prove that despite the hereditary advantages of being born in a position for nurture, some variations in the genetic blueprint will find their way to being successful regardless. Arguably, these would be much better variations than their nurtured counterparts, given that they met or surpassed the systems in place despite being disadvantaged.

I believe that, as with many other binary arguments, the truth lies in the middle.

There is some basic degree of intelligence within any member of the human species. Severe under-nurture of it (e.g., the deprivation of language or education at an early age) can hamper it, and at worst create changes in the underlying biological wiring of the individual to do away with it, whilst over-nurture of it (e.g., enriched early childhood environments) can potentiate it and lead to social mobility.

But there is also some uncontrollable pre-birth and semi-controllable post-birth randomness to intelligence due to how genome sequencing works. When a baby is born, copying errors occur naturally during the DNA replication process from parent to child. On average, each person acquires roughly 60 to 70 of these genetic errors according to Kong et al. (2012).

While these errors might seem infinitesimal relative to the 3 Billion base pairs of the human genome, they imply that even if there is some shared baseline that can be under/over-nurtured, the inherent stochasticity of DNA sequencing means over a long enough horizon, natural variations in intelligence and most biological systems will occur naturally.

The good news is that the human body actively reshapes how its genome is read and accessed based on its experiences to remain competitive, especially those that have a particularly strong psychological or biological impact. This is the science and study of epigenetics, and it means that while one may not get to choose which genetic mutations affect intelligence, it is possible to cultivate or otherwise nurture experiences that reshape nature downstream.

As to whether one has the circumstances or means to do so is a different question and having made the argument above, it's clearer how you could justify saying talent is equally distributed but opportunity isn't.

You might be wondering now how does this relate to the unified vs. fractured representation of concepts in neural networks from before.

If we look at the exercise in networks through these assumptions about intelligence, I think it's fairly clear that there are some components missing to achieving a general purpose unified representation system (AKA AGI).

First, as noted above, there is some deterministic aspect to how intelligence starts out. Nature has elegantly figured out a combination in the arrangement of neurons and organs in the human body that results in intelligent beings. This is the biological foundation where our oldest ancestor must've started: 'ground-zero' intelligence.

Ground-zero intelligence was characterized by the comprehension of only the most basic things. For example, line segmentation for internal representations of different types of objects. The type of things that a baby can process mentally but not articulate or put to meaningful use.

Arguably, ground-zero type intelligences still exist today amongst animals, as they are the basic building block for non-intelligent, semi-intelligent, and intelligent life (e.g., bacteria -> animals -> humans).

Here, I first thought of intuitively writing that I at some point nature 'found' the right starting primitive and stuck with it. However, this attributes nature agency, which isn't right. Instead, it's more appropriate to say ground-zero intelligences evolved out of being the best for the constraints for survival at the time.

Paraphrased, steps in the evolutionary ladder weren't climbed, they were found thanks to natural selection.

This is important because it's the opposite of how AI systems are being made as of 2025. They're trained from a top-down approach, reinforcing directly the behaviors or pattern recognition needed to solve specific, trackable problems, when originally these problems were solved from the bottom-up, as the result of naturally emergent systems of cognition that were simply responding to the realities and pressures of their environments.

I believe that to make AGI we 1) will not be working in pro of an optimization problem, with clearly defined correct and incorrect answers, and instead 2) will need to replicate the environments and constraints that led to intelligence emerging biologically and instead find ways to make minimum viable systems (i.e., the earliest forms of life) live eons of years inside of them, evolving naturally as we did until they reach our level of intelligence.

Interestingly, some semblances of this scenario have been floated as a way of how we might come to end ourselves, hypothesizing if we let an agent run for thousands of years in one day of human time it will make a plot for human dominance due to a misinformed objective function and execute it from there on out.

I think 2) above could actually be far worse. If we created environments that replicated our world and let them run for longer than our society has developed (assuming these environments model fully the physics of the world and work carefully around the constraints of information theory), it's very hard to tell what we might find.

I would argue that if we did indeed figure out how to make stateful replicas of our world that run faster than we do, that might be the highest technological peak humanity can reach. Inside, we'd find that these societies would all converge into the same technologies and theories, recursively creating their own replicas until we shut the original one down.

The above opens many interesting questions about entropy and the order that would arise if things were to be let run for long enough, but for the purposes here, I'll tidy up concluding that our current frameworks for the creation of intelligence are misaligned and merely 'convenient'.

When the scaling laws 'clicked' back in the days of AlexNet, we rode the compute wave focusing on how data aggregation and data expression could be used to create intelligent systems. Now, I think we need to re-think from first principles what are the constraints that led to the emergence of intelligence and simulate those environments and circumstances.

As mentioned in the video, if we don't make the underlying model architectures learn from the bottom up they won't form the right internal representations of concepts needed to generalize across domains. This seems to be part of the underlying intelligence algorithm, and I think it's an exciting road to see how it will be developed. I'd bet it won't be thought out by a mathematician or AI person, though. It's too abstract for that. I place better odds at that it will be some group of generalists from a different field solving a similar problem. I just hope we'll get to see it within our lifetimes.

Footnotes

-

It is worth noting that depending on how one defines intelligence, this argument can be twisted plenty. I remember a quote from Naval Ravikant that read 'The only true test of intelligence is if you get what you want out of life'. By this definition, we might argue that intelligence is indeed a matter of nurture, as the emerging 1% example doesn't clarify if these 1% are entrepreneurs or scientists. Anyone with enough business context and perseverance can eventually become an entrepreneur. Is this applicable for scientists as well? I believe yes, but to be precise when evaluating Naval's argument we'd want to look at how many in the 1% did something intellectually taxing and how many simply were focused or disciplined enough to make something that people wanted. I would still argue that given the sheer amount of problems that need solving to get to the 1% from a disadvantaged position, anyone who can do so is intelligent. ↩